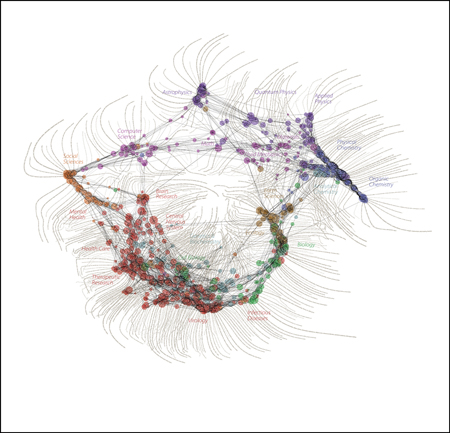

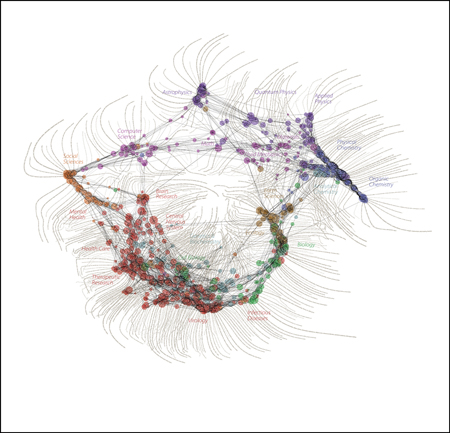

A visualization showing the structure of scientific knowledge.

by Boonsri Dickinson

To show how information builds up and flows among scientific disciplines, Columbia University computer scientist W. Bradford Paley, along with colleagues Kevin Boyack and Dick Klavans, categorized about 800,000 scholarly papers into 776 areas of scientific study (shown as colored circular nodes) based on how often the papers were cited together by other papers. Paley then grouped those nodes by color under 23 broader areas of scientific inquiry, from mental health to fluid mechanics.

1 Social Scientists Don’t Do Chemistry

The bigger a node is, the more papers it contains. Heavily cited papers appear in more than one node. Black lines connect any nodes that contain the same papers; the darker a link is, the more papers the connected nodes have in common. These links create the structure of the map and tend to pull similar scientific disciplines closer to one another.

2 Birds of a Feather

Paley refers to his map as a “feather boa”—the feathers being gently waving strings of key words that uniquely define each node’s particular subject matter. In tiny type, the word string “percutaneous tracheostomy, material review, autoimmune pancreatitis, and dialysis catheter,” for example, swirls off a node in the infectious disease area. Unlike the carefully calculated placement of the nodes, the team’s arrangement of the word strings on the page was left mostly to aesthetics.

3 The Road to Knowledge

The map doesn’t show the road to breakthrough discoveries, but it can be used to determine which areas of science are most closely connected to one another, as well as which are the most—and least—intellectually vital and productive. Advances in mathematics are few. Medicine, on the other hand, dominates the lower half of the map.

4 No Science Is an Island

…except maybe organic chemistry. One might assume that this bane of premed students is closely tied to medicine, but the map shows that the route from organic chemistry to health care requires more than one pit stop through fields like analytical chemistry, physical chemistry, biology, and even earth sciences. In fact, all of chemistry is a bit of an inside job. The links between the nodes of different chemistry disciplines are darker than other links because the disciplines tend to contain the same papers.

5 The Friendster Element

On the map, computer science is linked more closely to social sciences like psychology and sociology than to applied physics. “If you trust it for a minute, it does make intuitive sense,” Paley says. Social networks like Friendster depend heavily on software programs, while social scientists frequently rely on computers for statistical analysis.

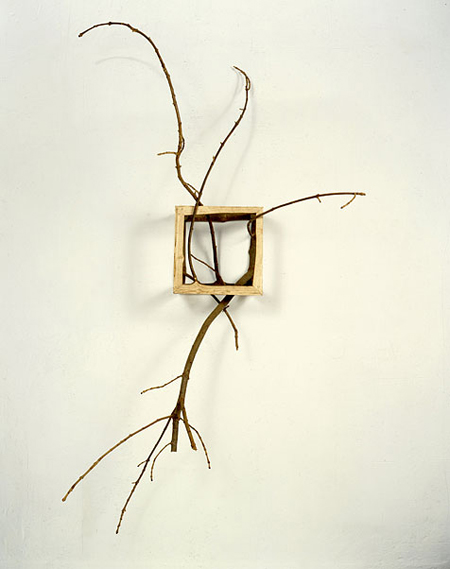

The Tree of Science

from The Golden Encyclopedia, 1959