Alan Weisman

Earth Without People, 2005

Given the mounting toll of fouled oceans, overheated air, missing topsoil, and mass extinctions, we might sometimes wonder what our planet would be like if humans suddenly disappeared. Would Superfund sites revert to Gardens of Eden? Would the seas again fill with fish? Would our concrete cities crumble to dust from the force of tree roots, water, and weeds? How long would it take for our traces to vanish? And if we could answer such questions, would we be more in awe of the changes we have wrought, or of nature’s resilience?A good place to start searching for answers is in Korea, in the 155-mile-long, 2.5-mile-wide mountainous Demilitarized Zone, or DMZ, set up by the armistice ending the Korean War. Aside from rare military patrols or desperate souls fleeing North Korea, humans have barely set foot in the strip since 1953. Before that, for 5,000 years, the area was populated by rice farmers who carved the land into paddies. Today those paddies have become barely discernible, transformed into pockets of marsh, and the new occupants of these lands arrive as dazzling white squadrons of red-crowned cranes that glide over the bulrushes in perfect formation, touching down so lightly that they detonate no land mines. Next to whooping cranes, they are the rarest such birds on Earth. They winter in the DMZ alongside the endangered white-naped cranes, revered in Asia as sacred portents of peace.

If peace is ever declared, suburban Seoul, which has rolled ever northward in recent decades, is poised to invade such tantalizing real estate. On the other side, the North Koreans are building an industrial megapark. This has spurred an international coalition of scientists called the DMZ Forum to try to consecrate the area for a peace park and nature preserve. Imagine it as “a Korean Gettysburg and Yosemite rolled together,” says Harvard University biologist Edward O. Wilson, who believes that tourism revenues could trump those from agriculture or development.

As serenely natural as the DMZ now is, it would be far different if people throughout Korea suddenly disappeared. The habitat would not revert to a truly natural state until the dams that now divert rivers to slake the needs of Seoul’s more than 20 million inhabitants failed—a century or two after the humans had gone. But in the meantime, says Wilson, many creatures would flourish. Otters, Asiatic black bears, musk deer, and the nearly vanquished Amur leopard would spread into slopes reforested with young daimyo oak and bird cherry. The few Siberian tigers that still prowl the North Korean–Chinese borderlands would multiply and fan across Asia’s temperate zones. “The wild carnivores would make short work of livestock,” he says. “Few domestic animals would remain after a couple of hundred years. Dogs would go feral, but they wouldn’t last long: They’d never be able to compete.”

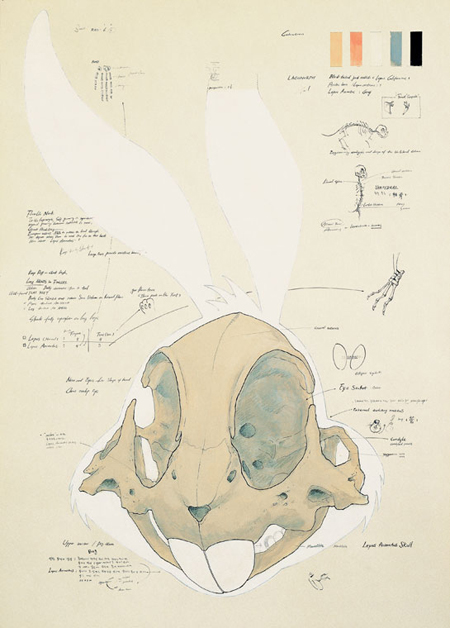

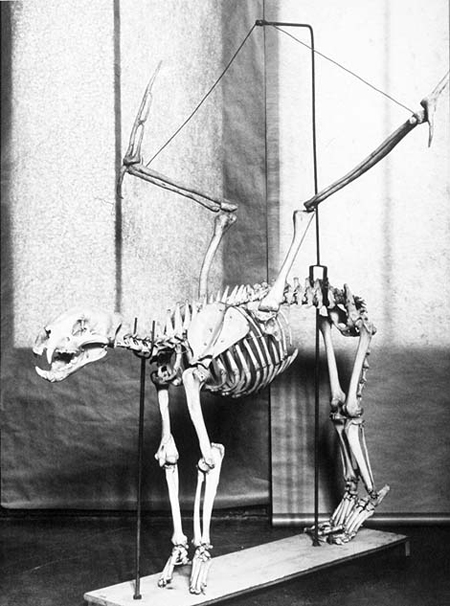

If people were no longer present anywhere on Earth, a worldwide shakeout would follow. From zebra mussels to fire ants to crops to kudzu, exotics would battle with natives. In time, says Wilson, all human attempts to improve on nature, such as our painstakingly bred horses, would revert to their origins. If horses survived at all, they would devolve back to Przewalski’s horse, the only true wild horse, still found in the Mongolian steppes. “The plants, crops, and animal species man has wrought by his own hand would be wiped out in a century or two,” Wilson says. In a few thousand years, “the world would mostly look as it did before humanity came along—like a wilderness.”

The new wilderness would consume cities, much as the jungle of northern Guatemala consumed the Mayan pyramids and megalopolises of overlapping city-states. From A.D. 800 to 900, a combination of drought and internecine warfare over dwindling farmland brought 2,000 years of civilization crashing down. Within 10 centuries, the jungle swallowed all.

Mayan communities alternated urban living with fields sheltered by forests, in contrast with today’s paved cities, which are more like man-made deserts. However, it wouldn’t take long for nature to undo even the likes of a New York City. Jameel Ahmad, civil engineering department chair at Cooper Union College in New York City, says repeated freezing and thawing common in months like March and November would split cement within a decade, allowing water to seep in. As it, too, froze and expanded, cracks would widen. Soon, weeds such as mustard and goosegrass would invade. With nobody to trample seedlings, New York’s prolific exotic, the Chinese ailanthus tree, would take over. Within five years, says Dennis Stevenson, senior curator at the New York Botanical Garden, ailanthus roots would heave up sidewalks and split sewers.

That would exacerbate a problem that already plagues New York—rising groundwater. There’s little soil to absorb it or vegetation to transpire it, and buildings block the sunlight that could evaporate it. With the power off, pumps that keep subways from flooding would be stilled. As water sluiced away soil beneath pavement, streets would crater.

Eric Sanderson of the Bronx Zoo Wildlife Conservation Society heads the Mannahatta Project, a virtual re-creation of pre-1609 Manhattan. He says there were 30 to 40 streams in Manhattan when the Dutch first arrived. If New Yorkers disappeared, sewers would clog, some natural watercourses would reappear, and others would form.Within 20 years, the water-soaked steel columns that support the street above the East Side’s subway tunnels would corrode and buckle, turning Lexington Avenue into a river.

New York’s architecture isn’t as flammable as San Francisco’s clapboard Victorians, but within 200 years, says Steven Clemants, vice president of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, tons of leaf litter would overflow gutters as pioneer weeds gave way to colonizing native oaks and maples in city parks. A dry lightning strike, igniting decades of uncut, knee-high Central Park grass, would spread flames through town.

As lightning rods rusted away, roof fires would leap among buildings into paneled offices filled with paper. Meanwhile, native Virginia creeper and poison ivy would claw at walls covered with lichens, which thrive in the absence of air pollution. Wherever foundations failed and buildings tumbled, lime from crushed concrete would raise soil pH, inviting buckthorn and birch. Black locust and autumn olive trees would fix nitrogen, allowing more goldenrods, sunflowers, and white snakeroot to move in along with apple trees, their seeds expelled by proliferating birds. Sweet carrots would quickly devolve to their wild form, unpalatable Queen Anne’s lace, while broccoli, cabbage, brussels sprouts, and cauliflower would regress to the same unrecognizable broccoli ancestor.

Unless an earthquake strikes New York first, bridges spared yearly applications of road salt would last a few hundred years before their stays and bolts gave way (last to fall would be Hell Gate Arch, built for railroads and easily good for another thousand years). Coyotes would invade Central Park, and deer, bears, and finally wolves would follow. Ruins would echo the love song of frogs breeding in streams stocked with alewives, herring, and mussels dropped by seagulls. Missing, however, would be all fauna that have adapted to humans. The invincible cockroach, an insect that originated in the hot climes of Africa, would succumb in unheated buildings. Without garbage, rats would starve or serve as lunch for peregrine falcons and red-tailed hawks. Pigeons would genetically revert back to the rock doves from which they sprang.

It’s unclear how long animals would suffer from the urban legacy of concentrated heavy metals. Over many centuries, plants would take these up, recycle, redeposit, and gradually dilute them. The time bombs left in petroleum tanks, chemical plants, power plants, and dry-cleaning plants might poison the earth beneath them for eons. One intriguing example is the former Rocky Mountain Arsenal next to Denver International Airport. There a chemical weapons plant produced mustard and nerve gas, incendiary bombs, napalm, and after World War II, pesticides. In 1984 it was considered by the arsenal commander to be the most contaminated spot in the United States. Today it is a national wildlife refuge, home to bald eagles that feast on its prodigious prairie dog population.

However, it took more than $130 million and a lot of man-hours to drain and seal the arsenal’s lake, in which ducks once died minutes after landing and the aluminum bottoms of boats sent to fetch their carcasses rotted within a month. In a world with no one left to bury the bad stuff, decaying chemical containers would slowly expose their lethal contents. Places like the Indian Point nuclear power plant, 35 miles north of Times Square, would dump radioactivity into the Hudson long after the lights went out.

Old stone buildings in Manhattan, such as Grand Central Station or the Metropolitan Museum of Art, would outlast every modern glass box, especially with no more acid rain to pock their marble. Still, at some point thousands of years hence, the last stone walls—perhaps chunks of St. Paul’s Chapel on Wall Street, built in 1766 from Manhattan’s own hard schist—would fall. Three times in the past 100,000 years, glaciers have scraped New York clean, and they’ll do so again. The mature hardwood forest would be mowed down. On Staten Island, Fresh Kills’s four giant mounds of trash would be flattened, their vast accumulation of stubborn PVC plastic and glass ground to powder. After the ice receded, an unnatural concentration of reddish metal—remnants of wiring and plumbing—would remain buried in layers. The next toolmaker to arrive or evolve might discover it and use it, but there would be nothing to indicate who had put it there.

Before humans appeared, an oriole could fly from the Mississippi to the Atlantic and never alight on anything other than a treetop. Unbroken forest blanketed Europe from the Urals to the English Channel. The last remaining fragment of that primeval European wilderness—half a million acres of woods straddling the border between Poland and Belarus, called the Bialowieza Forest—provides another glimpse of how the world would look if we were gone. There, relic groves of huge ash and linden trees rise 138 feet above an understory of hornbeams, ferns, swamp alders, massive birches, and crockery-size fungi. Norway spruces, shaggy as Methuselah, stand even taller. Five-century-old oaks grow so immense that great spotted woodpeckers stuff whole spruce cones in their three-inch-deep bark furrows. The woods carry pygmy owl whistles, nutcracker croaks, and wolf howls. Fragrance wafts from eons of mulch.

High privilege accounts for such unbroken antiquity. During the 14th century, a Lithuanian duke declared it a royal hunting preserve. For centuries it stayed that way. Eventually, the forest was subsumed by Russia and in 1888 became the private domain of the czars. Occupying Germans took lumber and slaughtered game during World War I, but a pristine core was left intact, which in 1921 became a Polish national park. Timber pillaging resumed briefly under the Soviets, but when the Nazis invaded, nature fanatic Hermann Göring decreed the entire preserve off limits. Then, following World War II, a reportedly drunken Josef Stalin agreed one evening in Warsaw to let Poland retain two-fifths of the forest.

To realize that all of Europe once looked like this is startling. Most unexpected of all is the sight of native bison. Just 600 remain in the wild, on both sides of an impassable iron curtain erected by the Soviets in 1980 along the border to thwart escapees to Poland’s renegade Solidarity movement. Although wolves dig under it, and roe deer are believed to leap over it, the herd of the largest of Europe’s mammals remains divided, and thus its gene pool. Belarus, which has not removed its statues of Lenin, has no specific plans to dismantle the fence. Unless it does, the bison may suffer genetic degradation, leaving them vulnerable to a disease that would wipe them out.

If the bison herd withers, they would join all the other extinct megafauna that even our total disappearance could never bring back. In a glass case in his laboratory, paleoecologist Paul S. Martin at the University of Arizona keeps a lump of dried dung he found in a Grand Canyon cave, left by a sloth weighing 200 pounds. That would have made it the smallest of several North American ground sloth species present when humans first appeared on this continent. The largest was as big as an elephant and lumbered around by the thousands in the woodlands and deserts of today’s United States. What we call pristine today, Martin says, is a poor reflection of what would be here if Homo sapiens had never evolved.

“America would have three times as many species of animals over 1,000 pounds as Africa does today,” he says. An amazing megafaunal menagerie roamed the region: Giant armadillos resembling armor-plated autos; bears twice the size of grizzlies; the hoofed, herbivorous toxodon, big as a rhinoceros; and saber-toothed tigers. A dozen species of horses were here, as well as the camel-like litoptern, giant beavers, giant peccaries, woolly rhinos, mammoths, and mastodons. Climate change and imported disease may have killed them, but most paleontologists accept the theory Martin advocates: “When people got out of Africa and Asia and reached other parts of the world, all hell broke loose.” He is convinced that people were responsible for the mass extinctions because they commenced with human arrival everywhere: first, in Australia 60,000 years ago, then mainland America 13,000 years ago, followed by the Caribbean islands 6,000 years ago, and Madagascar 2,000 years ago.

Yet one place on Earth did manage to elude the intercontinental holocaust: the oceans. Dolphins and whales escaped for the simple reason that prehistoric people could not hunt enough giant marine mammals to have a major impact on the population. “At least a dozen species in the ocean Columbus sailed were bigger than his biggest ship,” says marine paleoecologist Jeremy Jackson of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. “Not only mammals—the sea off Cuba was so thick with 1,000-pound green turtles that his boats practically ran aground on them.” This was a world where ships collided with schools of whales and where sharks were so abundant they would swim up rivers to prey on cattle. Reefs swarmed with 800-pound goliath grouper, not just today’s puny aquarium species. Cod could be fished from the sea in baskets. Oysters filtered all the water in Chesapeake Bay every five days. The planet’s shores teemed with millions of manatees, seals, and walrus.

Within the past century, however, humans have flattened the coral reefs on the continental shelves and scraped the sea grass beds bare; a dead zone bigger than New Jersey grows at the mouth of the Mississippi; all the world’s cod fisheries have collapsed. What Pleistocene humans did in 1,500 years to terrestrial life, modern man has done in mere decades to the oceans—“almost,” Jackson says. Despite mechanized overharvesting, satellite fish tracking, and prolonged butchery of sea mammals, the ocean is still bigger than we are. “It’s not like the land,” he says. “The great majority of sea species are badly depleted, but they still exist. If people actually went away, most could recover.”

Even if global warming or ultraviolet radiation bleaches the Great Barrier Reef to death, Jackson says, “it’s only 7,000 years old. New reefs have had to form before. It’s not like the world is a constant place.” Without people, most excess industrial carbon dioxide would dissipate within 200 years, cooling the atmosphere. With no further chlorine and bromine leaking skyward, within decades the ozone layer would replenish, and ultraviolet damage would subside. Eventually, heavy metals and toxins would flush through the system; a few intractable PCBs might take a millennium.

During that same span, every dam on Earth would silt up and spill over. Rivers would again carry nutrients seaward, where most life would be, as it was long before vertebrates crawled onto the shore. Eventually, that would happen again. The world would start over.

Originally appeared in Discover Magazine, February, 2005. Copyright © 2005 by Alan Weisman.