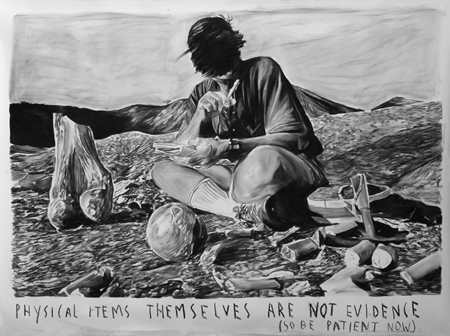

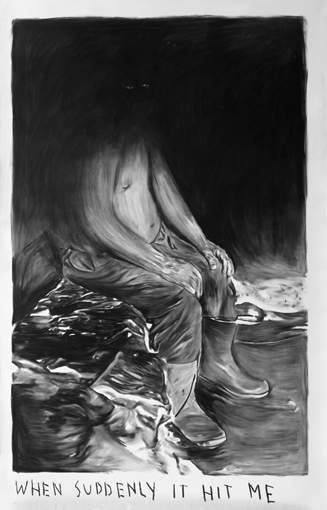

Curdin Tones

final exam | overview sculptures, 2003

Making and Knowing. On the Work of Curdin Tones.

by Janneke Wesseling, Leffond, May 2007

Man is afflicted with a mania to order and structure the world. The garden must be weeded, the land cultivated. Everything around us is manufactured, made. Not only in the city, but also outside of it, in nature or what’s left of it. The need to intervene, cultivate, re-arrange, emerges over and over. Like the creation of the ‘foraging landscape’ and ‘recreation zones’ in the Lange Bretten, the green belt between Amsterdam West and Halfweg through which Curdin Tones cycles on his way to his studio. The greenery must be organised and contained; asphalt is laid, trees felled, water features laid out. Our environment is in a constant state of flux, constantly altering the benchmarks for our actions. A cycling path is suddenly re-routed, the intersection has become a roundabout. And we change with them.

Tones (Tschlin, Zwitserland, 1976) understands only too well the passion to order, the fervour to impose human will on material. When will and material converge, enormous satisfaction is produced. Which applies equally to a well-shaped knife and a successful sculpture.

As a child, Tones watched a carpenter shape a straight shelf to fit a bowed wall. The carpenter drew the curvature of the wall onto the shelf with a pencil held flush to the wall. At this moment, the difference between straight and crooked was unmasked. The carpenter shaved away the excess wood. The linear had become the curvilinear.

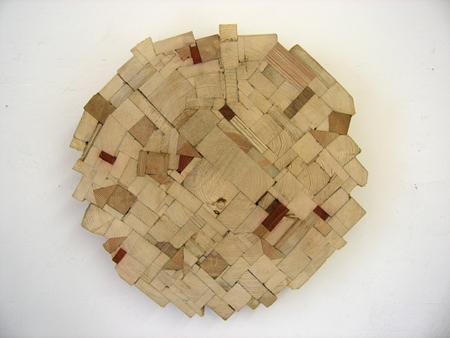

Tones produced his first sculptures (2003) from pinewood packing case wood. He screwed three straight boards, appropriately warped, to one bent one. This resulted in a single volume, a compressed beam. One sees that the ‘beam’ is hollow from the side. Tones made three such sculptures, as is his wont: he produces variations on an idea, resulting in a series. Two of which are on show at the exhibition in Enschede.

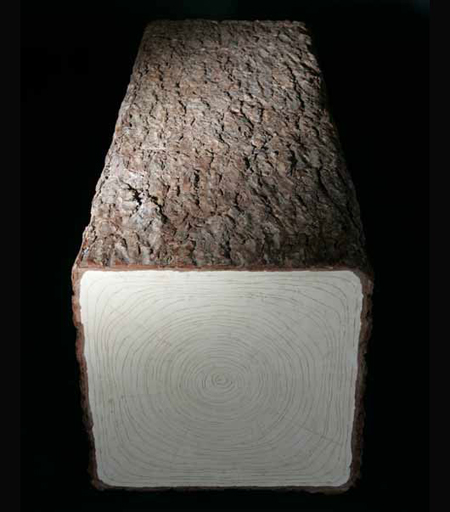

Material dictates form. In the book Eigen Grond, that Tones produced on the occasion of his graduation presentation at the Rietveldacademie, he writes: “Wood is a material that has grown. The growth of the tree depends on where the tree stands. The growth locus determines the height of the tree, hardness of the wood and number of knots. The wood of one tree may be harder on one side than the other. Wood from the root and crown sections also differ in strength. Sapwood and hardwood serve different functions within the tree, thus having different degrees of hardness. While the wood dries out, these anomalies cause tensions. If a beam is finally allocated one place and one function, knowledge of where the tree grew may be vital. A craftsman who cut and sawed the tree himself knows the wood and its qualities so he can use it to better effect. When fresh wood is used inappropriately it can split, break and resist its assigned function. The awareness that no two lengths of timber are the same is crucial during construction so as to make best use of the planks.”

In the sculptures that resulted, fashioned from wood grown on mountainsides, Tones again explored the tension between wood as natural material and worked it according to traditional methods. He sawed various trunks lengthwise into four, planning the sawed edge of the sections smooth. Then he affixed the edging. The long timber sections look vulnerable and organic laid on the ground.

Tones wants to make things, objects that are physically present. He wants to make three dimensional objects, even though most of his pieces are presented lying on the ground. He loves the stubbornness of the material. He searches for ways of heightening the experience of the material.

Sculpture demands a slow concentration, a different way of looking. It is a kind of leisureliness when compared to how we live and navigate the city, accustomed as we are to digital media and lightning-speed, fleeting impressions. Tones is fascinated by the rural landscape of his youth. Life in the country has weight, torpidity; time works differently. Admittedly, things age here, but at another pace.

Curdin Tones

without title, 2004

arolla pine (208 x 13 x 12 cm)

foto: P.Cox

without title, 2004

arolla pine (23 x 409 x 1.8 cm)

foto: P.Cox

Long ago, there was no difference between the artist and the craftsman. The word techne, from which our word ‘technology’ derives, not only referred to the practice of craftsmanship, but also to art. The cabinet maker and the potter, and the master builder, sculptor or painter were all called technites. This changed with Plato and Aristotle. Philosopher Gerard Visser writes: “Aristotle distinguished between man and animal: animals live by experience (empeira), but man lives by technique and reasoning (technekai logismois). Techne is the extraordinary means of poiesis that produces, from what it brings forth, in order to cause (aition). Techne is not production as such, the proficiency grown of experience, but knowing the reason why (dioti). Nowadays we understand this knowledge only in terms of rationality and causality, the seed of which was planted by Aristotle”.

In other words, technology was once more than knowing in terms of rationality and causality, it was knowing why. The same Aristotle elsewhere spoke of techne as episteme, a way of knowing or recognising that is not only rational knowing, but a knowledge that produces truth.

This means, however miraculous it might sound to us, that truth can result from making (poiein) something, and that a product can be true, can possess a truth. Technology once was not something rational as in our day. Visser : “Anything that transposes something from not-being to being is poiesis. Poiesis underlies the products of all technai. All craftsmen who bring something into being are poietai. Technology, we could say, is thus also poetic. And art is, reversed, a form of technology; not because the artist would also be a craftsman […], but because the work of both is real.”

Since Plato, who asserted that a work of art is the embodiment of imitation and illusion and that it has nothing to do with truth or knowledge, and, since Aristotle, art and technology have gradually grown apart. Until they became two completely separate areas. Visser: “Art and technology are identified with the mutually exclusive spheres of the illusory and the true, the ideal and real, the emotional and the intellectual, the irrational and the rational.” Art became uprooted because its ability to think, to get to know the world and discover truth, was denied.

Since Modernism and the avant-gardes of the last century, artists have been reclaiming the ability to think, whether this is intuitive or rational thought or both simultaneously. In the tradition of the avant-garde, the artist accepts nothing as a given. It is his task to question all suppositions about art and art practice, and his position in society, again and again. Since then, artists have appropriated a critical-theoretical approach that is generally considered as an integral element of their practice. Art itself is increasingly considered a form of research, as an activity directed at knowledge acquisition. There is mounting attention, both among artists and theoreticians, for the cognitive function of the artwork: art as a way of getting to know reality.

This does not mean that art and technology or art and science have since drawn closer together again (although there are some signs pointing in that direction). But perhaps greater scope has been shaped for the idea that the artwork can offer insight into, or knowledge of, reality. A knowledge that is not directed at a clearly delineated objective, at applicability, but art as a means of knowing why.

This lies at the heart of Tones’ work. His ambition is to learn about the materials with which he works and our attitudes to them, to attain insight into our way of being in the world. Just as the craftsmen of his native village have an intimate knowledge of pinewood and put this knowledge into practice every day, Tones, by giving these materials a new form endeavours to bring their essence to light.

It is an attempt to render the spirit of wood, plaster, concrete or stone visible or tangible through human action. Making, poiein, is knowing.