Steve Tomasula

(GENE)SIS, 2000

In the Beginning, God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness,” and He formed man of clay and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, punning adam, Hebrew for “man,” with adamah, “earth.” Soon afterwards, Adam, in God’s image, created language–Man’s first creation–his every utterance the birth of another word as he cried out names for the other animals in Eden. Some seven thousand generations after Adam (according to DNA theory), Eduardo Kac creates the transgenic art work Genesis, re-enacting these primal conflations of language and earth and by doing so critically reanimating the myth that is most central to the West’s conception of humankind, nature and progress.

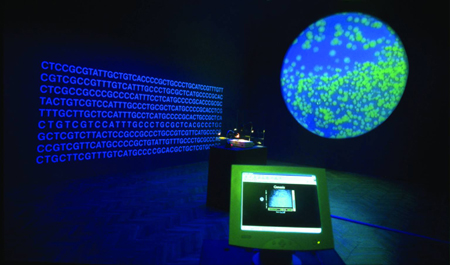

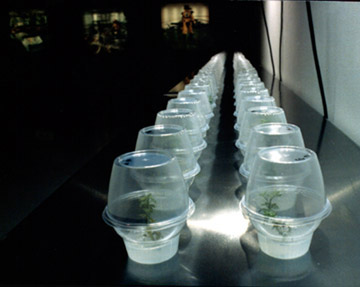

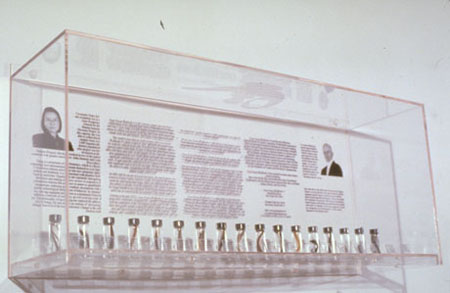

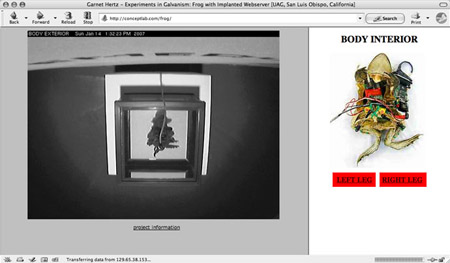

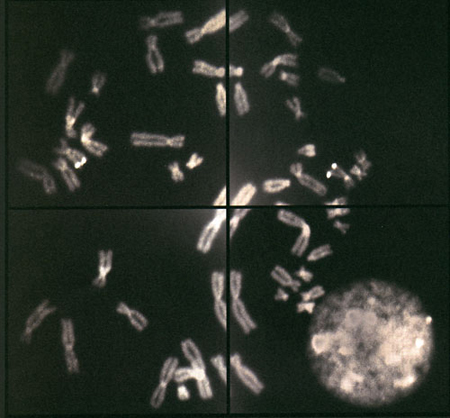

Entering the exhibition space of Genesis, the viewer stands before a large projected image: a circular field suspended in blackness and reminiscent of astronomical photographs–a sky filled with galaxies, each composed of millions of suns–circled by how many Edens? As in those photographs, though, scale belies creation. For the God’s-eye view afforded by Kac’s Genesis comes from a micro-videocamera not a telescope, and the “galaxies” are actually bacteria in a petri dish. Each bacterial body is written in the same genetic language as our bodies, as are all bodies, even if some of them carry a gene unlike the genes of any body. That is, in Kac’s eden, some of the animals carry a synthetic gene he fashioned, not from mud, but by arranging genetic material into an order that did not exist in Eden, and today does not exist in nature.

Specifically, Kac’s genesis begins with the genetic alphabet: the chemical bases, Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine and Thymine, abbreviated as A, G, C, T. By chaining together, these chemical bases make up the rungs of the DNA molecule, the double-helix whose sequences of letters–genes–serve as both blueprint and material for the creation of life. Just as the dot-dot-dot | dash-dash-dash | dot-dot-dot of Morse Code can form a message, here an S-O-S, sequences of three genetic bases, e.g., AGC | GCT | ACC, form particular amino acids. Particular strings of amino acids form particular proteins, while particular proteins form the particular cells of particular organisms, be they a serpent, an apple, or the rib of a man. Thus each DNA molecule is both material and message, both the book and its content: a book that is its message embodied. Alter this sequence, and the new message will produce a different book: a mutation, for example, that brings into existence the larynx that allows human speech, or a Frankenfruit, as environmentalists refer to genetically engineered fruits and vegetables. Or the cells that make up the bacteria in Genesis.

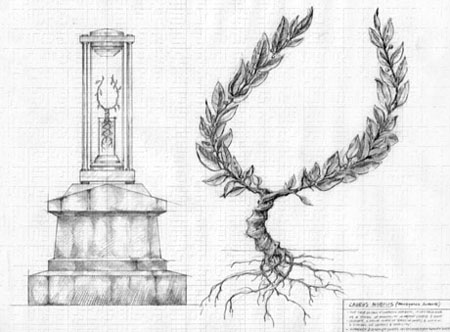

While the sequence of letters that make up the “artist gene” in Genesis are artificial, though, they were not arbitrary. Significantly, they embody a sentence from the Biblical Genesis: “Let man have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.” To translate this natural language into the language of the cell, the AGCTs of DNA, Kac used Morse Code as an algorithm. The dots and dashes of Morse Code easily translate into the 1s and 0s used by a digital computer to represent the alphabet–information in a form that can easily be sent around the globe or across the microscopic distances within an integrated circuit. Similarly, in Genesis, information is given its physical corollary: after translating the biblical passage into the dots and dashes of Morse Code, the dots were replaced by the genetic base Cytosin (C); dashes were substituted with Thymine (T); word spaces were replaced by Adenine (A); while letter spaces replaced by Guanine (G). This unique string of AGCTs constitutes a gene that does not exist in nature, an “art gene.”

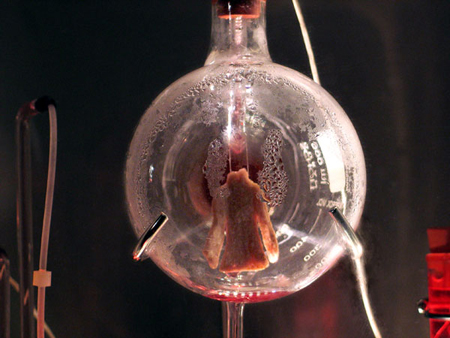

The “art gene” carrying the coded biblical passage was then combined with a protein that glows cyan when illuminated by ultraviolet light. Both protein and art gene were inserted into a species of E. coli similar to that found in the human intestinal tract but which is unable to live outside of the medium in the petri dish. Art and science are thus collapsed into one another through two characteristics of E.coli: its ability to carry DNA from unrelated organisms, and its facility for self-replication. Together they make E. coli useful as a living factory for genetically engineered products, such as insulin; they also allow it to function as a microscopic “scribe” copying out the narrative carried within the “artist gene.” These genetically engineered bacteria were then placed in a petri dish along with a strain of E. coli that will glow yellow under an ultraviolet lamp but that do not carry the Genesis gene.

Like one of the seventy scholars who first translated Genesis from Hebrew into Greek, then, Kac has translated Genesis into a new language, and like them, embodied it in a “book” that is both a product and reflection of his times. Consider the illuminated manuscript, and how its body expressed medieval culture. Its materials were all natural, its text linked to the earth by inks and pigments extracted from minerals, berries or flowers, and scratched onto sheepskin with quills from a goose. Writing the text was an act of physical as well as mental labor. The words themselves were written with no separation just as creation was thought to be a single parchment, God’s book, an uninterrupted Great Chain of Being from the lowest dregs to the celestial spheres where, as Augustine put it, “the angelic and blessed pass their nontime reading a language without syllables, a text that is unequivocal and eternal because it is the face of the Word itself.” In Eden, it was believed, God, man, and animals all spoke the same language in which words and things had the direct one-to-one correspondence Adam gave them. Or as Emerson later put it, “Every word was once an animal.” In this way, written words were natural objects: visible traces of God’s mind, as was the rest of the world, shapes that could be read for meaning just as a later age taught itself to read the history of weather in the rings of trees. Letters, words, sentences, pages merged into sacred books of mysteries serene as the primum mobile in their gilt capitals and painted illustrations, their ornaments and imposing page layouts, displayed on high altars for the adoration of the faithful.

Few of the materials of Kac’s “book” are natural–even its biological materials are highly mediated by technology. Yet this fact is barely noticeable, seeing as it has become “natural” for us to spend most of our time in artificial light, artificial heat, eating and sleeping not when we are hungry or tired but when the clock says it is time. In the dim temple-like atmosphere of a gallery, viewers are drawn closer by the beauty of Genesis, its projection of the petri dish, round as a rose window, and luminous as stained glass. A diffuse blue light reflects off lettering on walls that complete what can be thought of as a triptych: on the right-hand panel are the words extracted from the biblical text, “Let man have dominion over every living thing.” The left-hand panel displays its genetic translation–the string of AGCTs used to encode the biblical passage in the bacteria, printed out in a computer’s block letters without separation just as genes are found before mapping reveals the mystery of their identity and function. The gallery space is thus transformed into a polyglot in which the same passage is presented in three languages: a natural language, a language of chemicals, and Morse Code, that first electronic language, whose first transmitted words–“What hath God wrought?”–ushered in an age of global communication. Reading this polyglot, we begin to understand how to a contemporary sensibility all the world is a text–even unto the lowest dregs commonly found in the colon–and how, like that world, Kac’s book is densely coded. Standing at a pulpit that presents the petri dish as if it were an open book, viewers/readers realize that what they have been admiring in Kac’s staging is the beauty of bacteria, the beauty of the flower in the crannied wall, that if understood, could reveal all in all.

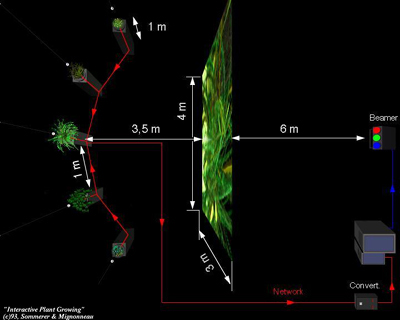

Yet the artistry and significance of Genesis is not in Kac’s creation of aesthetic objects. Rather, its meaning unfolds as its viewers participate in the social situation he has orchestrated. Visiting Genesis at home via the Internet, or by using a computer in the gallery that is likewise networked through the Internet, viewers constitute a world-wide community able to write upon Kac’s text. By clicking their mouses, they control an ultraviolet light trained on the petri dish. When they do, the “rose window” flashes blue as if animated by a primordial spark, the bacteria glow. The bacteria carrying the text of Genesis as part of their bodies give off cyan light; those without it give off yellow. More importantly, as viewers activate the ultraviolet light they become Kac’s co-authors by accelerating the natural mutation rate of the bacteria. Some descendants retain their original color, others exchange plasmids with one another and give off color combinations, such as green, while still more lose their color. Operating the light to observe this evolution within Kac’s microcosm, the viewer realizes how impossible it is to walk in the Garden without altering it. Looking down upon this microcosm, finger on the button, it’s hard to not want to alter the bacterial garden if for no other reason than to see what will happen. Understanding that changing the bodies of the bacteria also changes the message they carry, we realize that the seduction of Genesis is also the seduction of science–word and body, art and world–all intimately linked.

No one knows the origins of Genesis–the biblical text Kac incorporates into his microcosm. For centuries it circulated in various forms along with other creation myths until it was written down, sometime in the 8th century BCE. Thus, as is said of the Odyssey and other scribal texts, the “author” was the aggregate of all the people who wove and rewove oral teachings, reworking, corrupting and embellishing the stories to fit their circumstances. This is why the inconsistencies we find in Genesis today, including two contradictory stories of creation, were of so little consequence to those first “users” that they could all be taken up and passed on together. As biblical historian Karen Armstrong writes, believers of all three monotheist religions regarded the creation of a myth in the best sense of the word: as a symbolic account which helped people to orient themselves to ontological, and theological questions as well as their present circumstances. It was only long after Genesis was written down that it began to ossify into an official doctrine believed to be factually true.

Indeed, contemporary scholars distinguish between the open text of scribal cultures, and the closed text of print cultures: that is, between the text that is continually turning into new versions of itself, and the text that has reached its final form and is thus closed to revision. In the middle ages it was common for readers to add their comments to a manuscript by writing between its lines, or in its margins, altering a text as they saw fit and passing it on as though the alterations were part of the original book. Since “original” was thought to be “that which was there since The Origin,” writing was an act of proliferation, not the “creation” of a unique utterance. Conversely, reading was the act of eliciting from a text that which had remained hidden, or unspoken. In this sense, every text was ripe with more than it said, with myths being the most open of texts, the most incomplete in that myths held the most potential meaning. Conversely, the authority of a text resided in its ability to remain fecund, to be the first word, not the last word. Midrash, the Jewish practice of scriptural explication, was (and to this day still is) the practice of incorporating all of the previous commentary into the text. The text itself was conceived of always being in need of refiguring to present circumstance. That is, the point of Midrash was not literal interpretation, but to guide people through the complexities and contradictions of their own lives, their own moment in history. The text in this sense was always being made new. And since making it new was figured as a way of life, it was obvious who had the authority to say what the text meant. It was obvious who had the responsibility to understand what it meant: Everyone.

Similarly, Kac’s Genesis opens itself up as a myth for our times in the sense of poet John Dryden’s description of translations as “transfusion,” i.e. the transfusion of new life into an old text. The thousands of people who transmitted the Biblical Genesis as oral teachings, its co-authors, finds its corollary in Kac’s co-authors: the thousands of engineers, scientists and technicians upon whom Genesis’s existence depends. Their labor offers up a vocabulary of “gene splicing,” and “interactivity,” and “nucleotide polymorphisms” without which Kac’s Genesis couldn’t be written. Incorporating the traces of this labor as layers in his own palimpsest, Kac creates an allegory of Origins, of Nature, and man’s relation to them. By enabling ordinary readers all over the globe to join in the rewriting of this text, he stresses the communal nature of allegory–how authorship itself has become communal in an age when physical diaspora is mitigated by global communication, a development anticipated by Morse Code. Indeed, at the turn of our century, the increased speed and interaction of global communication has accelerated an evolution of reading as the practice of reading between the lines, to reveal all that is unsaid. Grande Historie has become petite histoires in which the body has been the only closed book–a naturally impermeable text that could be re-read, but not re-written.

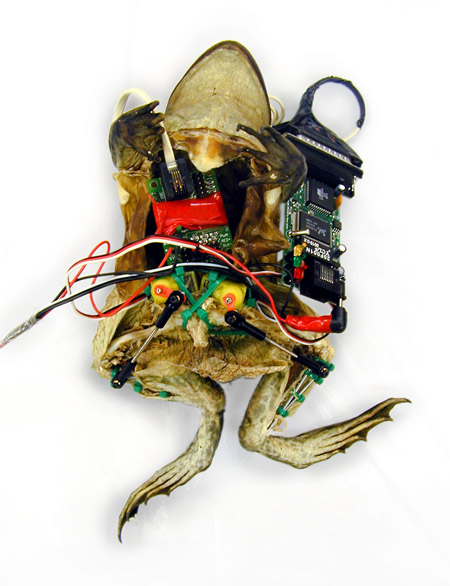

But biotechnology has opened up ever wider spaces for new authors to write between the lines, just as biotechnology revealed how the structure of E. coli bacteria would allow Kac to copy in the text of Genesis. With the sequencing of the gene, the practice of rewriting “the fish of the sea, fowl of the air and every other living thing” is becoming so common as to precipitate a shift in our conception of nature analogous to the shift in the conception of earth at the advent of the telescope. Those critics of Copernicus who refused to accept that the earth revolved around the sun, Thomas Khun wrote, were not entirely wrong. To them, “earth” meant “fixed, immovable position.” Looking through Galileo’s telescope and seeing evidence for the earth’s orbit and rotation thus entailed a semantic leap as well as a shift in perspective. The world could only change, after Galileo, to the degree that language changed. Similarly, it’s becoming easy to think of animals not as fixed “objects” in nature but as re-arrangeable packets of DNA. Over the past decade, the list of patents issued world-wide for bioengineered products is long and varied and includes the combination of cow embryos with human genes in attempts to grow human replacement parts and tomatoes with the genes of a codfish to make them less susceptible to freezing. Chickens carry the genes of the salmon while sheep receive tobacco genes, and worms, after Methuselah, have been engineered to increase their life span to the equivalent of 600 human years. Using a genetically altered bacteria (trade name “messenger”) basic crops like wheat and corn are engineered to protect themselves by killing insects.

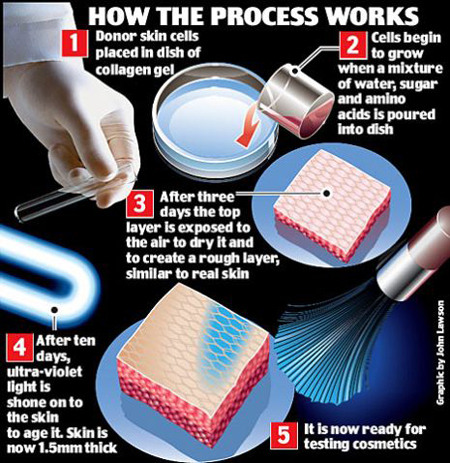

As our garden becomes populated with more, and more extreme, varieties of transgenic plants and animals, as these techniques are increasingly applied to humans, can the Adamic conception of the self remain any more constant? Dramatic advances such as the cloning of our primate cousins receive the most attention. But it is perhaps the thousands of small steps that coalesce, like myths, into habits of mind that have the most profound effects: calls for genetic national identity cards; the permission we give on the back of our driver’s license for our bodies to become recyclable material, permission that allowed Matthew Scott to receive the hand of a cadaver by transplant, the hand that John Doe, it’s previous “owner” had used to write his name, to clasp in prayer, now taking up a new name, new prayers. Artificial skin; artificial bone. In petri dishes like the one used in Genesis, researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have been able to grow cartilaginous ears and noses. Other labs claim to have discovered genes that determine everything from shyness to rape to altruism; first steps to practical applications soon follow, such as those taken by researchers at Yale University who by manipulating a gene identified as important to memory have created a strain of super-smart mice. Once the genetic tree of knowledge is completely sequenced, won’t we begin in earnest to rewrite genes to increase longevity, manipulate skin color, personality, indeed, all the traits that make us us?–to completely throw off the original sin and destiny of biology? Considering how conceptions of the self have had profound consequences for laws, for customs–for how people order society and conduct themselves and behave toward others–can we do without springboards to meditation such as Kac’s Genesis?

When the prospect of “personal evolution,” the prospect of individuals altering the genes of their descendants became a reality, the U.S. National Bioethics Advisory Commission turned to religious traditions as one factor in formulating its recommendations on how public policy should react. Its members cited the centuries people have used these traditions to guide their own behavior in the face of a changing world. By putting a global audience in collective control of his Genesis, by making their actions impinge upon an excerpt from the Biblical Genesis, Kac puts his audience in a position to consider tradition–or its erasure–as one factor in their response to the biological course we are just beginning to navigate. The evolution in a petri dish we communally alter underscores how the use of technology is not always planned, its consequences not always foreseen, nor benign. Standing in the box formed by the walls of Genesis, it’s easy for viewers to reverse the scale and think of themselves in the position of the bacteria with ultraviolet light streaming down (possibly through a hole in the ozone layer?). We’re invited to contemplate consequences of interfering with evolution when Kac translates, at the end of the exhibit, the DNA code of his original message back into English:

LET AAN HAVE DOMINION OVER THE FISH OF THE SEA AND OVER THE FOWL OF THE AIR AND OVER EVERY LIVING THING THAT IOVES UA EON THE EARTH

The now corrupted sentence calls to mind other literatures of constraint: those texts, such as Raymond Queneau’s One Hundred Million Million Poems, that have been generated out of a self-imposed rule. In Queneau’s work, a traditional fourteen-line sonnet is combined with ten other fourteen-line sonnets in such a way that any one line can be combined with the thirteen lines of any of the other sonnets. Thus, the poem as a whole allows the meaning held as a potential within the dull mass of language to emerge: a potential of 1014 sonnets, a quantity of text, as François Le Lionnais notes, “far greater than everything man has written since the invention of writing, including popular novels, business letters, diplomatic correspondence, private mail, rough drafts thrown into the wastebasket, and graffiti.” Conversely, Kac’s corruption also calls to mind literatures of non-constraint, such as Luis Borges’s hypothetical 1,000 monkeys typing on 1,000 typewriters in the hopes of producing an exact copy of Don Quixote. With over 3,000,000,000 genetic letters in the book that is the human, Genesis asks us to consider the ramifications of typos–and their transmission to future generations. Unbridled, typos cumulate into gibberish quickly, for as Alice learned in Wonder Land, even a sentence of only ten words has 3,628,800 combinations, only one or two of which will make sense. Mutating any three letter word, say APE, into another three letter word, say MAN, by randomly switching one letter at a time takes thousands of generations to hit the right combination. But if the changes are governed by the constraint that each step must make sense, then the mutation can be made in only eight steps:

APE

ARE

ARM

AIM

RIM

RAM

RAN

MAN

Thus can be seen the apparent paradox of how the application of a constraint directs rather than stifles creation: the application of a constraint allows the process to ignore all the other constraints that would take it into other directions. Before man’s intervention, “survival of the fittest” was the dominate constraint under which changes were made to the book of each organism, including humans. While gene management has resulted in hairless Chihuahuas, seedless watermelons, indeed every strain of plant and animal not seen in Eden, it is only with the advent of bio-engineering that changes could be made that skip intervening steps. As Kac’s genesis illustrates, which potential literature will be offered up from among the thousands of potentials dormant in the mud of genetic language will depend on the constraints under which change operates. So it’s instructive to note how much of both the Biblical and the artist’s Genesis is concerned with lineage. Indeed, the Hebrew innovation in regards to the creation myths that circulated among the Israelites was to use them to shape their identity as a people–an identity traced through their bodies in a direct line of descendancy to Adam and Eve who were fashioned in the likeness of God. Thus, the mother of this people was named Eve, hawwa in Hebrew, related to hay “living,” the mother of all the living to follow. Reconstruction of genetic trees estimate that this woman–not the first woman, but the last woman every person now alive on earth is descended from–lived 143,000 years ago. For 5,700 generations, then, or 120,000,000 years if we count our ancestry back to the original cells, our biological identity has been shaped one letter at a time. In Kac’s Genesis, though, we see an icon for our new-found ability to rewrite ourselves–instantly, and in ways whose ramifications might not become apparent for generations. In an age when people are increasingly looking to chromosome stains to explain the difference between Cain and Able–as well as differences in sexual orientation, intelligence, personality, and hundreds of other human traits–Kac’s Genesis reminds viewers of the wisdom in tempering change with reflection.

That is, Kac’s Genesis calls us to consider which identity we are fashioning for ourselves, for our species, for nature, by the constraints we do or do not place on the potential literature of our bodies. Will the constraint of survival be replaced by economic gain? It wasn’t until 1967 that the U.S. Federal Trade Commission ruled that blood could be bought and sold. Up until then, blood with all of its metaphorical richness was considered a gift that could be given, like life, but was too sacred to be bought and sold. Today, the world market for blood is a $19-billion business and constitutes only a small segment of a bio-trade that includes on-line auctions for human eggs and sperm (www.ronsangels.com) among other human “components,” from whole corpses to fetal “products.”

Will the only constraint placed on these new potential literatures of the body be technological progress? Can constraints not be political? Does the ability to manipulate a gene, say for one of the 5,000 diseases now known to be inherited, carry with it the responsibility to do so? Who has the authority to alter the germ line of future generations? Who has the authority to determine the fate of the tens of thousands of embryos accumulating in storage tanks, the leftovers of reproduction technologies that allow couples to select the most genetically viable embryos while abandoning the rest? Will the constraints of bio-technology be social?–preferences for skin color or hair texture? Will they be legal?–such as the legal fights over who can copyright a person’s genetic information? Kac’s Genesis asks us to consider these issues by having us revisit the language of “dominion over every living thing.” By making us his co-authors, he emphasizes how the name we give ourselves can be in the spirit of “masters” or “caretakers” of our garden, how our collective actions will be our Midrash.

References

Armstrong, Karen. A History of God: The 4,000 Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993.

Bruns, Gerald L. Inventions: Writing, Textuality, and Understanding in Literary History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca. Genes, Peoples, and Languages. New York: North Point Press, 2000.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Queneau, Raymond. One Hundred Million Million Poems. Trans. John Crombie. Paris: Kickshaws, 1983.

Originally published in Dobrila, Peter T. (ed.). Eduardo Kac: Telepresence, Biotelematics, and Transgenic Art (Maribor, Slovenia: Kibla, 2000), pp.85-96. republished in : Thurtle, Phillip and Robert Mitchell (eds.), Data Made Flesh: Embodying Information (Routledge, 2003).

Steve Tomasula is the author of the novels VAS: An Opera in Flatland (Station Hill Press) and IN & OZ (Ministry of Whimsy Press). His short fiction has appeared widely and most recently in The Iowa Review, Fiction International, and McSweeney’s. Recent criticism and essays are included in Musing the Mosaic (SUNY Press); Data Made Flesh (Routledge); Leonardo (M.I.T. Press); the New Art Examiner, and other magazines both here and in Europe. He contributes often to The Review of Contemporary Fiction, the American Book Review, Rain Taxi, and the electronic book review. He holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Steve Tomasula is Assistant Professor of English, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana.