Homo Stupidus Stupidus; The Missing Meme

mei 27th, 2009Ida – Researchers from the University of Oslo have suggested the specimen, which was found 95 per cent complete, may be the root of anthropoid evolution, when primates were first developing the features that would evolve into our own.

Discovered in Germany, Ida is so well preserved that even the outline of its fur can be seen. An incredible 95 percent complete fossil of a 47-million-year-old human ancestor has been discovered and, after two years of secret study, an international team of scientists has revealed it to the world. The fossil’s remarkable state of preservation allows an unprecedented glimpse into early human evolution. Discovered in Messel Pit, Germany, it represents the moment before anthropoid primates–the group that would later evolve into humans, apes and monkeys–began to split from lemurs and other prosimian primates. This groundbreaking discovery fills in a critical gap in human and primate evolution.

– www.history.com –

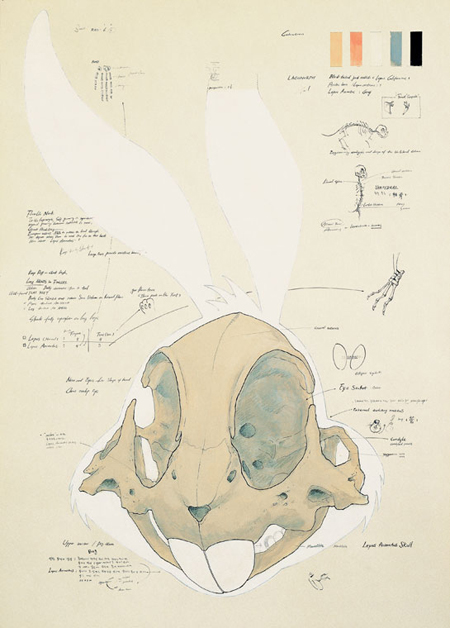

Maarten Vanden Eynde

Homo Stupidus Stupidus, 2009 A.D.

Richard Dawkins

The Ancestor’s Tale: A pergrimage to the dawn of Life, 2005

Just as we trace our personal family trees from parents to grandparents and so on back in time, so in The Ancestor’s Tale Richard Dawkins traces the ancestry of life. As he is at pains to point out, this is very much our human tale, our ancestry. The Ancestor’s Tale takes us from our immediate human ancestors back through what he calls ‘concestors,’ those shared with the apes, monkeys and other mammals and other vertebrates and beyond to the dim and distant microbial beginnings of life some 4 billion years ago. It is a remarkable story which is still very much in the process of being uncovered. And, of course from a scientist of Dawkins stature and reputation we get an insider’s knowledge of the most up-to-date science and many of those involved in the research. And, as we have come to expect of Dawkins, it is told with a passionate commitment to scientific veracity and a nose for a good story. Dawkins’s knowledge of the vast and wonderful sweep of life’s diversity is admirable. Not only does it encompass the most interesting living representatives of so many groups of organisms but also the important and informative fossil ones, many of which have only been found in recent years.

Dawkins sees his journey with its reverse chronology as ‘cast in the form of an epic pilgrimage from the present to the past [and] all roads lead to the origin of life.’ It is, to my mind, a sensible and perfectly acceptable approach although some might complain about going against the grain of evolution. The great benefit for the general reader is that it begins with the more familiar present and the animals nearest and dearest to us?our immediate human ancestors. And then it delves back into the more remote and less familiar past with its droves of lesser known and extinct fossil forms. The whole pilgrimage is divided into 40 tales, each based around a group of organisms and discusses their role in the overall story.

– Douglas Palmer –

Meme

Richard Dawkins first introduced the word in The Selfish Gene (1976) to discuss evolutionary principles in explaining the spread of ideas and cultural phenomena. He gave as examples melodies, catch-phrases, and beliefs (notably religious belief), clothing/fashion, and the technology of building arches.

Meme-theorists contend that memes evolve by natural selection (in a manner similar to that of biological evolution) through the processes of variation, mutation, competition, and inheritance influencing an individual entity’s reproductive success. Memes spread through the behaviors that they generate in their hosts. Memes that propagate less prolifically may become extinct, while others may survive, spread, and (for better or for worse) mutate. Theorists point out that memes which replicate the most effectively spread best, and some memes may replicate effectively even when they prove detrimental to the welfare of their hosts.

A field of study called memetics arose in the 1990s to explore the concepts and transmission of memes in terms of an evolutionary model. Criticism from a variety of fronts has challenged the notion that scholarship can examine memes empirically. Some commentators question the idea that one can meaningfully categorize culture in terms of discrete units.