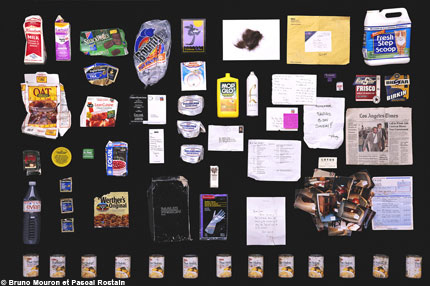

Pascal Rostain and Bruno Mouron

Hollywood’s trash and treasure, 2004

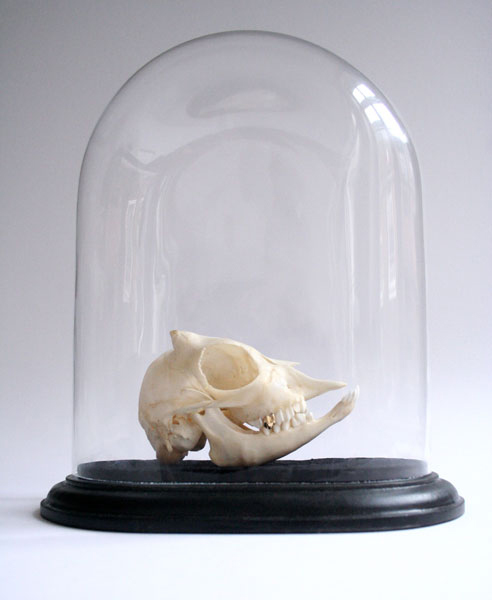

Ronald Reagan

Written by John Preston – Telegraph Magazine –

In 1988, French photographer Pascal Rostain had an idea. Or, to be strictly accurate, he nicked someone else’s. He read an article by a French sociologist who had set his students a project to examine the contents of 10 people’s rubbish bags. In garbage, the sociologist declared, could be found people’s true personality. Rostain wondered if it might take a little showbusiness twist. The next time he went on a job – to photograph the French singer Serge Gainsbourg – he took Gainsbourg’s bin-bags home with him. What he found astonished him. “It was like the key to Gainsbourg,” he says.

“Everything was completely distinctive: the bottles of Ricard, the packets of Gitanes. I felt as if I had a part of him in front of me.”

Soon Rostain and his partner, Bruno Mouron, were sifting through other famous people’s bin-bags. Brigitte Bardot came next, then French National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen. It may have been messy and smelly, but the results, the pair reckoned, were well worth the effort.

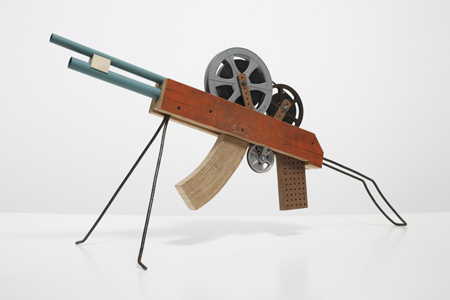

The magazine Paris Match suggested they try their luck in Los Angeles. In 1990, Rostain and Mouron flew to California with a map of the stars’ homes and a garbage collection schedule for Beverly Hills. “The first thing we would do was locate a suitable home,” says Rostain. “For example, Jack Nicholson’s or Bruce Willis’. Next, we would find out when the garbage was being collected and grab it before the truck came round.”

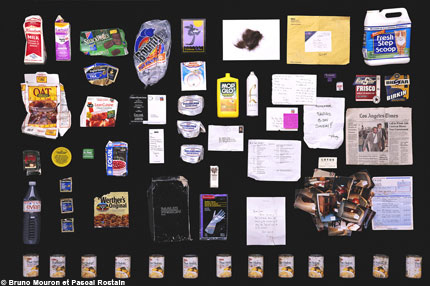

Taking someone’s rubbish is not illegal in America, but then came the awkward part. Rostain and Mouron wanted to do the photography in their Paris studio where they felt able to do their best work. They travelled back to France with three trunks of rubbish. When French customs officers demanded the trunks be opened, they recoiled in disgust, then went into a perplexed huddle and finally waved them through as harmless lunatics. Once home, they washed the contents of their trunks before spreading them out in neat lines to be photographed. They decided not to shoot anything that was either directly personal or medical – despite finding American Secret Service papers in Ronald Reagan’s rubbish listing his bodyguards and details of the weapons they carried. This puts them in quite a different league to more scurrilous scroungers such as Britain’s Benjamin Pell (aka “Benji the Binman”) who has made a speciality of raiding the rubbish bins of the famous, then selling the contents on to the tabloids, or even the original “garbologist” A. J. Weberman, who obsessively pillaged Bob Dylan’s bin for three years in the late 1960s. But there were still embarrassing slip-ups. In the rubbish of TV host Larry King, Rostain and Mouron found what they assumed were babies’ nappies. However, they turned out to be adult incontinence pads, which King indignantly denied were his. “We never wanted to create a scandal with what we were doing,” Rostain insists.

“They knew we won’t take pictures of empty Viagra packets, for example.”

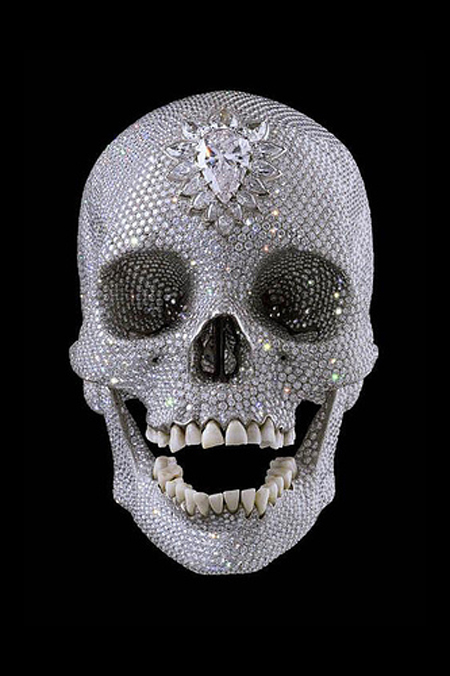

Sharon Stone

Yet what they have photographed proves to be both revealing and mysterious. While the objects themselves may be mundane, they throw up perplexing questions.

What, exactly did Sharon Stone do with 13 tins of pear halves? Was she simply creating a giant flan to delight her many friends? Or were darker, more fetishistic forces at work? Madonna, as one might expect, has glugged her way through a lavish array of bottled waters. However, there’s a faint poignancy about the empty pizza-for-one packet that nestles nearby.

Madonna

In Jack Nicholson’s rubbish we find a hearteningly large collection of empty booze bottles, but also a discarded hairbrush and comb. Does this mean that Nicholson’s creeping baldness has now reached the point where coiffure has become a thing of the past?

There’s nothing overtly strange about Elizabeth Taylor’s rubbish, but look more closely and a terrible bleakness starts to show through: the single-meal wrappers, the two bottles of non-alcoholic beer, the copies of the National Enquirer with articles about her in them. Is this how she spends her days, reading about herself in the scandal sheets while eating chicken enchiladas? It’s no wonder she chummed up with Michael Jackson; his life would appear to be equally empty, hedged about with ketchup wrappers and Cup O’Noodles.

It comes as no surprise to learn that several of Rostain and Mouron’s subjects – they won’t say who – recently bought the prints of their own rubbish at an exhibition in New York for $US6000 ($A8300) a piece, thus completing what even by Hollywood standards is a very peculiar cycle of self-regard.

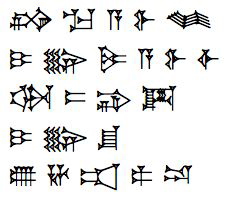

“My brother is an archaeologist,” says Rostain, “and he’s always telling me that if he could find the garbage of a Mayan family, then he would win a Nobel prize.

Oddly enough, I think what we are doing is significant. In 200 years’ time our pictures will provide a very useful guide to how certain people lived in the 21st century. So, you see, what we’re doing is fun – but it’s not only fun.”