Dark Energy

Maarten Vanden Eynde

Gravitational Bending, 2010

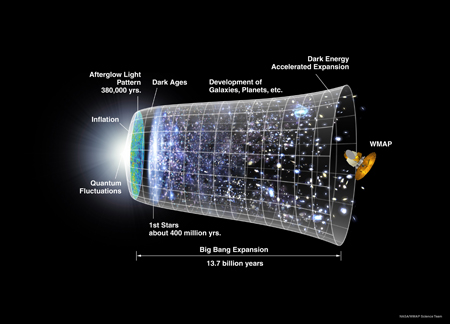

Even weirder than dark matter—the invisible stuff constituting most of the mass of the universe—is dark energy, a mysterious force pushing the universe apart at an ever-faster rate. Dark energy has been around for most of the history of the cosmos. “Nine billion years ago, dark energy was already wielding its repulsive influence on the universe,” explains Johns Hopkins University astrophysicist Adam Riess. But the repulsion didn’t exceed the force of gravity until 5 billion years ago, when cosmic expansion kicked into high gear and began accelerating.

A pioneering space mission called the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) delivered the first accurate account of the overall makeup of the universe. The answer is decidedly strange. Dark energy makes up 73 percent of the universe, dark matter another 23 percent. Atomic matter—everything around us and everything astronomers have ever seen—accounts for just 4 percent.

Comparing images from the Hubble Space Telescope’s high-end cameras with the WMAP heat signature map of the early universe, Riess and his colleagues retraced the growth history of the universe with unprecedented accuracy and depth. “It’s as if you mark the height of a child against a doorframe to measure growth spurts,” Riess says. For reasons as yet unknown, the antigravitational effects of dark energy are greater now than they were in the distant past. One theory, supported by the Hubble data, is that empty space is impregnated with residual energy from the Big Bang. As space expands, so does dark energy, while matter is spread out, weakening the inward pull of gravity.

Based on a text by Alex Stone

Chu Yun

Constellation, 2006

Galaxy made out of LED lights from various devices.