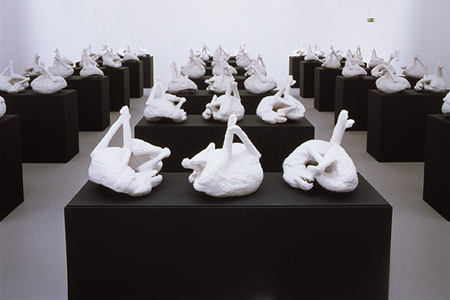

Allan McCollum

The Dog From Pompei, 1991

Cast glass-fiber- reinforced Hydrocal

Mount Vesuvius was blazing in several places…A black and dreadful cloud bursting out in gusts of igneous serpentine vapor now and again yawned open to reveal long, fantastic flames, resembling flashes of lightning, but much larger…Cinders fell…then pumice-stones too, with stones blackened, scorched, and cracked by fire …

The scene described by Pliny the Younger occurred on an August afternoon in 79 A.D. Of the more than 20,000 inhabitants in the city of Pompei, several hundred died that day in their homes and in the streets. The rest fled toward the sea.

The cavity of The Dog From Pompei was discovered November 20, 1874, in the house of Marcus Vesonius Primus, in the “Fauce,” the corridor at the entrance of the house. The house was located in Region VI, Insula 14, Nr. 20.

During the eruption, the unfortunate dog, wearing his bronze-studded collar, was left chained up at his assigned place to watch the house, and he suffocated beneath the ash and cinders.

Allan McCollum’s casts were taken directly from a mold made especially for the artist from the original second-generation cast presently on display at the Museo Vesuviano, in present-day Pompei.

Lost Objects, 1991

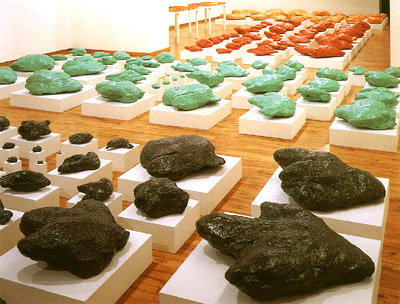

The Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah, 1993.

Allan McCollum’s series The Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah is a companion to the two series’ he’d done before—the Lost Objects (casts of dinosaur bones) and The Dog From Pompei— all created from gypsum casts of fossils and done in cooperation with natural history museums around the world. The Natural Copies are recastings of “natural casts” of dinosaur tracks found in the roofs of coal mines in central Utah, which are produced through a process of natural fossilization as follows:

(a) by dinosaurs walking over spongy beds of decaying vegetation (peat); (b) by the footprints being filled with sand, (c) by the accumulation of thousands of feet of additional sediment, which compressed the peat to help form coal and solidified the sand to sandstone; (d) by removal of the coal in mining operations so as to leave the tracks protruding downward into the mine; and finally, (e) by the geologist brushing away the residue of coal to expose the sandstone filling the original track.

McCollum offers his Natural Copies as an allegorical presentation of the narrative attached to other kinds of collectibles and fine art objects: in their various modes of production, exhibition, distribution, and collection; their use and exchange value; their function as markers of natural history or embodiments of cultural memory; their ambiguous status as found objects, cultural artifacts, scientific specimens or fine art objects; and their relation to local lore and folk stories of the region.

By reproducing the natural casts as artworks, McCollum intersects another narrative into the story. Originally discovered in the roofs of underground mines, the footprints’ inverted position offers the eerie experience of a dinosaur walking on the ground above one’s head, already suggesting the realm of the fantastic: monsters and exotic creatures from a primeval and forgotten past, treasures produced over the millennia and unearthed from the subterranean depths through the competative and determined search for “the rock that burns.” McCollum’s evocation of this narrative in the fine art context immediately transforms it into a metaphor for romantic views of the archaic and unconscious sources of human creativity, and at the same time suggests a symbolic shadow narrative that might underlie all social relations in communal labor.

Integral to his exhibitions is the accompanying display of multicolored photocopies of didactic literature the artist calls the Reprints. This other display of “copies” reiterates the metaphorical references to community organization, production, and dissemination in the real time of the exhibition space itself; it not only suggests an alternative to the convention of the expensive fine art catalogue, it simultaneously presents an exuberant, allegorical drama of repetition and production which imagines an uncanny continuity between the geological (natural) copying of tracks and traces from a prehistoric past and the mechanical and electronic endless copying of today.